I recently had the opportunity to talk about digital humanities in the context of new professional horizons, the rise of AI, and the urgent need to rethink language programs across the United States. Digital humanities is the practice of using digital tools to rethink how we consume, create, connect, and share knowledge. It is not about adding technology to existing courses. It is about redesigning learning so students produce meaning for real audiences, work across media, and connect their intellectual work to the world around them.

This matters deeply for language education. As we argued in our Conversation article on AI earbuds and the future of our profession, language learning is far more than a transactional skill. It is one of the most challenging, rewarding, and transformative human endeavors, grounded in identity, relationships, culture, interpretation, and the lived present. Digital humanities allows us to double down on these human dimensions while still embracing the digital reality our students inhabit. It shifts the focus from random input to relevant multimodal sources, from the grammar syllabus to meaningful tasks thoughtfully supported by technology, and from the typical classroom presentation to a product with public relevance.

In a recent reflection on institutional change and uncertainty, I wrote about how moments of disruption force us to ask better questions about what higher education is for. Digital humanities offers one powerful answer. It bridges the need to cultivate critical skills with the need to reconnect the university to society and to new ways of communicating and creating knowledge. When students build Story Maps about local transportation equity, publish blog posts that examine complex global and local issues, or design language games tied to their community, they are not just learning Spanish. They are learning how to observe, interpret, design, and contribute.

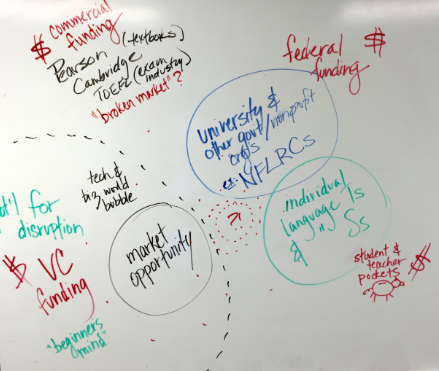

This is also where digital humanities becomes a strategic response to declining enrollments in language programs. Students are drawn to relevance. They want to see how their learning connects to real issues, real communities, and real careers. Digital humanities reframes language study as a laboratory for digital communication, intercultural problem solving, and civic engagement. It makes visible the transferable skills that language educators have always cultivated but rarely named in ways that resonate beyond our field.

Digital humanities, then, is both inward and outward. Inward, it transforms how we select and scaffold input, how we assess learning, and how students understand their own intellectual agency. Outward, it positions the language classroom as a hub of public facing scholarship, community partnership, and digital creativity. In a time when AI can generate text in seconds, what becomes valuable is not only speed, but the ability to pair that speed with depth, meaning, and connection.

If we take this seriously, digital humanities is not an add on to language programs. It is a redefinition of them.