“Este programa te ayudará a evaluar tu nivel de competencia en las lenguas que sabes de acuerdo con seis niveles de referencia definidos en el Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas (MCERL). La escala de referencia, creada por el Consejo de Europa en 2001 es reconocida como un sistema estándar europeo para evaluar la competencia lingüística de cada individuo y es empleado por sistemas educativos nacionales, organismos certificadores y empleadores. Cuando respondas a las preguntas recuerda que se trata tan solo de un procedimiento de auto-evaluación y que los resultados solamente reflejan parte de tus destrezas, ¡es sólo un juego! Solo tú sabes hasta donde llegan realmente tus habilidades” (Consejo de Europa)

Author: gabiguillen

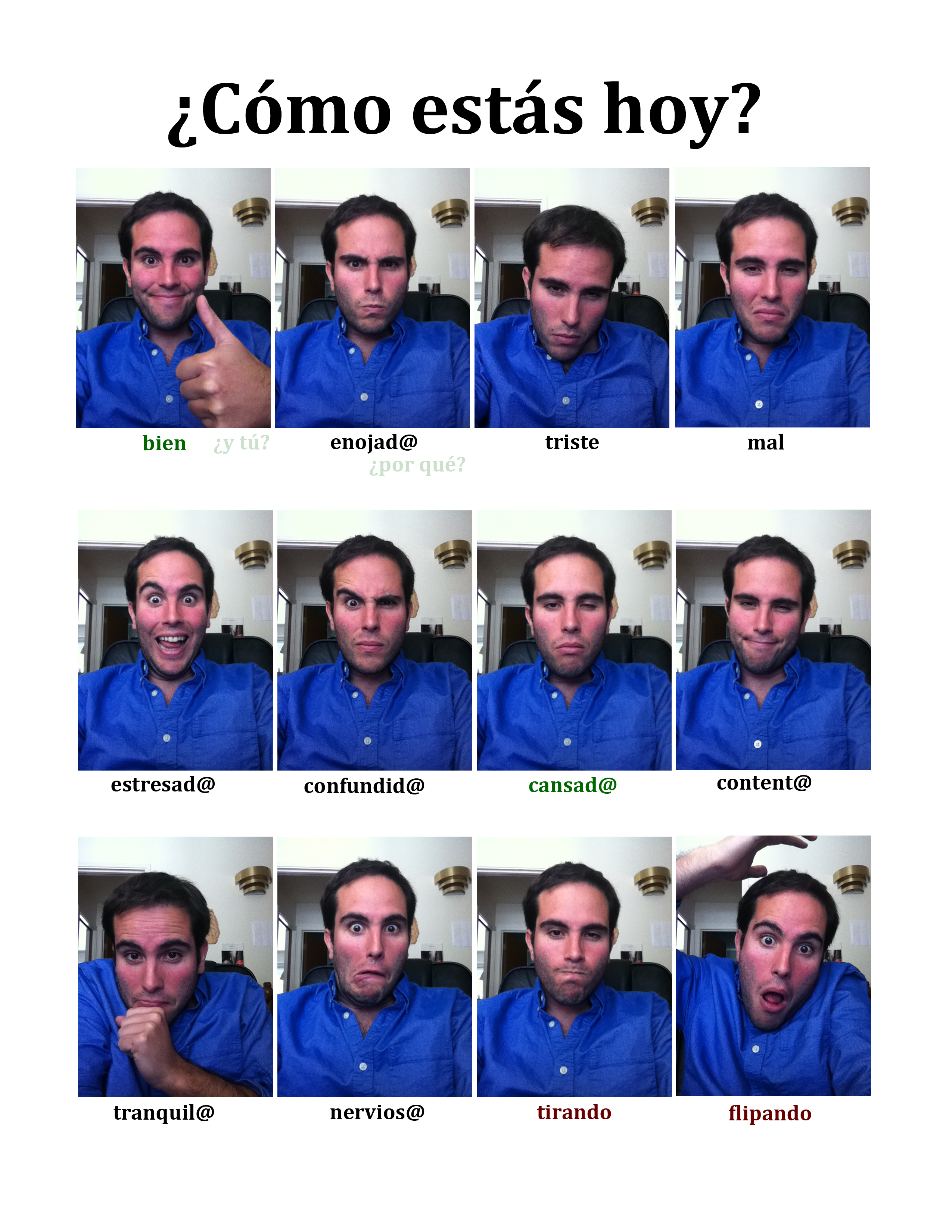

How do you feel today?

Procrastination at work: Warming up for Spanish Beginners

Watched pot never boils?

“A good deal of current theorizing in SLA is built on the principle that a watched pot never boils. This approach, with its stress on interaction and meaningful communication, responds well to the problems of the overly conscious “monitor over-user” (Krashen 1978), whose rules get in the way of fluent communication, and is in harmony with research findings that grammatical competence derived through formal training is not a good predictor of communicative skills (Canale and Swain 1980, Savignon 1972, Tucker 1974, Upshur and Palmer 1974). However, the partial independence of grammatical competence from the other components of communicative competence is also reflected in the ability of second language learners like Wes to communicate well without much grammatical control. For such learners, interaction, which they are already good at, is no panacea. The “watched pot” analogy begins to fall apart, because learning a second language is not as simple as boiling water but has at least as many aspects and dimensions as preparing a meal. First, one must turn on the heat and assemble the ingredients. Social and affective factors have a lot to do with providing the heat, and the interaction which they engender provides manageable data for the learner (Long, forthcoming), but surely that is not the end of the endeavor. The learner must cook the complementary courses of the meal, and in the case of grammar that means processing data received through interaction: analyzing them, formulating hypotheses (which may not be expressible as formal rules but may nevertheless be conscious at some stage of the process, at least through the ability to recognize nativelike linguistic strings), and testing those hypotheses against native speaker speech and native speaker reactions. These are of course psychological processes, but the idea that if affective factors are positive then cognitive processes will function automatically, effortlessly, and unconsciously to put together conclusions about grammar is overly optimistic. Interest and attention are additional minimum requirements if the sauce is to come out as well as the main course, and most language learners would agree that hard work is involved as well” (Schmidt 1983, pp. 172-173)

Learning as foraging

“In foraging for food, signals indicating reduced glucose levels cause an animal’s nervous system to generate an incentive motive ro acquire food. …..The desire to acquire certain knowledge or skill similarly constitutes an incentive motive that a learner must translate into activity in order to learn. In other words, a learner must do things in order to learn.” (Schumann, 2001, p. 21)

The illusion of learner-centered classes

Finishing a presentation for tomorrow, I ran into an interesting paper from 2006: A paradigm shift of Learner-Centered Teaching Style: Reality or Illusion? (Arizona Working Papers):

“The learner-centered approach is praised in research and practice to address individual learners’ needs. However, the findings of this study along with previous research studies indicate that instructors still use traditional, teacher-centered styles in university settings.” (Liu et al 2006:86)

I could agree. Even our communicative classes are still teacher-centered and yet, they can be productive. The paradigm is, nevertheless, shifting. As it should be.